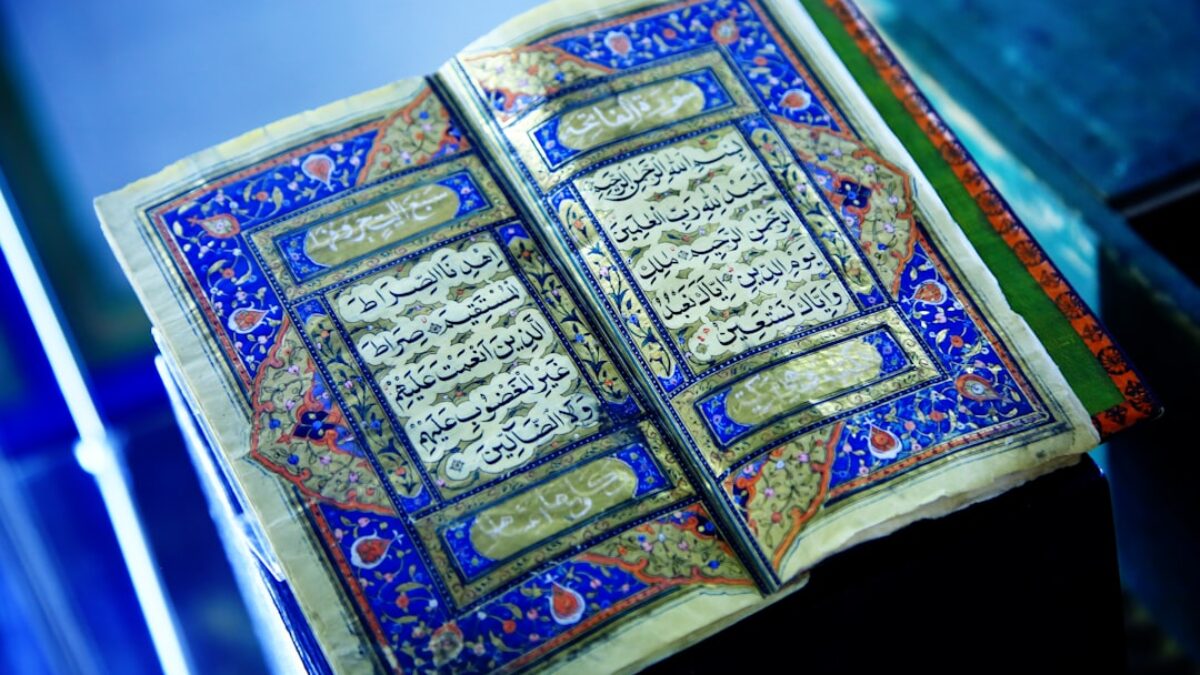

Approaching the intellectual legacy of the great Islamic scholars is not merely an academic exercise; it is a spiritual and intellectual odyssey that can reshape how we understand revelation, reason, and the human quest for meaning. From the luminous pages of Iḥyāʾ ʿUlūm al-Dī of Imām al-Ghazālī to the intricate legal dialectics in al-Muwaṭṭaʾ of Imām Mālik, the works of classical and contemporary ʿulamāʾ form a living library that continues to inform Muslim thought and practice. Yet, many students—whether in universities, madrasas, or self-directed circles—struggle with where to begin, how to read, and what to prioritize. This master guide distills a roadmap that balances reverence for the tradition with the rigor of modern research skills, equipping you to study their works, biographies, and teachings with clarity and purpose.

Understanding Islamic Scholars and Their Intellectual Ecosystem

The Definition and Role of an ʿĀlim

In Islamic terminology, an ʿālim (pl. ʿulamāʾ) is literally “one who possesses knowledge” (ʿilm). Yet this is not a casual accolade. Classical manuals—such as Ibn Ṣalāḥ’s Muqaddimah—outline a hierarchy of expertise:

- ʿĀlim al-ʿAqīdah: masters of creedal theology (kalām)

- ʿĀlim al-Fiqh: specialists in jurisprudence and its evidential bases (uṣūl)

- ʿĀlim al-Ḥadīth: experts in prophetic traditions, rijāl (biographical evaluation), and jarḥ wa-taʿdīl (criticism and accreditation)

- ʿĀlim al-Tafsīr: exegetes who weave grammar, law, and theology into Qurʾanic commentary

- ʿĀlim al-Taṣawwuf: scholars of spiritual purification and inward wayfaring

Understanding these categories prevents reductionist readings of a scholar’s corpus and highlights interdisciplinary connections that once defined the pre-modern riwāq (study circles).

The Genealogy of Knowledge: Isnād and Intellectual Lineage

Islamic intellectual culture is inseparable from isnād—chains of transmission that function as both a scholarly credential and a spiritual genealogy. When Imām al-Bukhārī narrates a ḥadīth, he opens a window into a living isnād that stretches back to the Prophet ﷺ. Similarly, the ijāzah system ensures that commentaries on Sharḥ al-Waraqāt or Kutub al-Tawḥīd do not float in an intellectual vacuum but are anchored in authenticated chains.

Key Components of Studying Islamic Scholars’ Works

1. Primary Sources: Manuscripts, Critical Editions, and Reliable Translations

Manuscript Repositories

Digital portals such as al-Maktabah al-Shāmilah, Shamela.ws, and AhlalHdeeth.com host thousands of scanned manuscripts. Yet not every scan is equal. Prioritize:

- Critical Editions (e.g., Dār al-Minhāj, Muʾassasat al-Risālah) that collate multiple nuṣakh (manuscripts) and provide footnotes on variant readings.

- Authenticated e-versions marked with takhrīj (referencing) by recognized scholars like Nūr al-Din ʿItr or Ṣalāḥ al-Din al-Munajjid.

- Parallel Arabic-English texts for intermediate students (e.g., Fons Vitae’s bilingual Risālat Qushayriyya).

Reference Table: Critical Editions vs. Popular Prints

| Criterion | Critical Edition | Popular Reprint |

|---|---|---|

| Base Manuscripts | Multiple early makhṭūṭāt | Often a single late print |

| Marginalia | Full taʿlīqāt and takhrīj | Limited or absent |

| Price & Availability | Higher cost, selective | Low cost, widely available |

2. Scholarly Biographies: Sīrah, Ṭabaqāt, and Modern Historiography

Biographical dictionaries are the backbone of contextual reading. Begin with:

- Al-Dhahabī’s Siyar Aʿlām al-Nubalāʾ for chronological depth.

- Al-Subkī’s Ṭabaqāt al-Shāfiʿiyyah al-Kubrā for legal-school affiliations.

- Contemporary monographs (e.g., Jonathan Brown’s Hadith: Muhammad’s Legacy) that reevaluate classical narratives through source-critical lenses.

While reading, map each scholar’s chronotope: political milieu, patronage networks, and the ʿulamāʾ-state dialectic. This prevents anachronistic judgments—Was al-Ghazālī “anti-philosophy” or rather a constructive critic of Aristotelian epistemology?

3. Methodologies of Engagement: From Passive Reading to Lived Application

Step 1 – Survey the Corpus

Before delving into Kitāb al-Waraqāt, catalog every work attributed to the scholar. Tools like Kashf al-Ẓunū or modern bibliographies (e.g., OCLC Arabic Union Catalog) provide a macro view. Note which texts are:

- Muṣannafāt (original compositions)

- Mukhtaṣarāt (abridgements)

- Sharḥ (commentaries)

- Ḥāshiyah (marginal glosses)

Step 2 – Identify Foundational Primers

Scholars often wrote layered curricula. Ibn Abī Zayd al-Qayrawāī’s Risālah is the gateway to Mālikī fiqh, while Al-ʿAqīdah al-Ṭaḥāwiyyah anchors creed studies. Build a reading ladder:

- Beginner – primer with interlinear translation.

- Intermediate – classical commentary plus modern footnotes.

- Advanced – compare multiple commentaries, trace dalāʾil (evidences) back to Qurʾan and Sunnah.

Step 3 – Close Reading and Textual Analysis

Adopt a three-pass system:

- Diagnostic Pass: Skim headings and subheadings, noting keywords in Arabic.

- Analytical Pass: Identify dalīl, taʿlīl (reasoning), and khilāf (juridical disagreement).

- Synthetic Pass: Reconstruct the scholar’s manhaj (methodology) and test it against contemporary issues.

Benefits and Importance of Deep Engagement

Spiritual Formation: Turning Texts into Inward Realities

Ṣūfī scholars like Ibn ʿAjībah insist that “knowledge is not what is memorized by the tongue, but what is actualized by the limbs.” When we study the adab (etiquette) sections of Iḥyāʾ, we are not merely accumulating facts; we are training the soul in khushūʿ and taqwá.

Intellectual Humility and Critical Thinking

Encountering sophisticated kalām arguments or uṣūlī distinctions exposes the student to the limits of language and the contingency of interpretive choices. This fosters epistemic humility—a counterweight to the certitude culture prevalent online.

Community Impact: From Individual Reader to Collective Resource

Communities plagued by shallow fatwa-shopping benefit from members trained in manhaj al-taḥqīq (methodology of verification). A student who has traced Imām Mālik’s principle of maṣlaḥah can explain why certain fatāwa shift across contexts, thus reducing ideological polarization.

Practical Applications: From Theory to Daily Routine

Designing a Personalized Study Schedule

Weekly Micro-Cycle (Example)

- Mon & Thu – 60 mins Arabic reading of Sharḥ al-Ṭaḥāwiyyah with muhādathah (peer discussion)

- Tue – 45 mins comparative fiqh: Mālik vs. Ḥanafī on bayʿ al-wafāʾ

- Wed – 30 mins biography: read entry on Imām al-Shāfiʿī in Siyar and summarize

- Fri – 90 mins live webinar with a scholar on uṣūl al-tafsīr

- Sat – reflective journaling: connect insights to family life

Tools and Technologies

- Zotero + Arabic Plugin for citation management

- Maktabah Shamela Search Syntax (e.g.,

@ابن تيمية تفسيرrestricts results to Ibn Taymiyyah’s exegetical works) - Obsidian Canvas to build mind-map of a scholar’s terminological network

Building a Living Study Circle (Majlis ʿIlmī)

A sustainable circle requires:

- Clear covenant: attendance, adab, and shared goals.

- Rotating leadership: each week a different member prepares questions.

- Service component: translating short fatwas for local mosques or writing blog posts in accessible English.

Frequently Asked Questions

Post Comment